Funding and Reports

Investing in Salt Lake City

Community Reinvestment agencies are authorized by the State to direct funding to specific parts of a municipality through “project areas,” which are established through a multi-step, public process and guided by project area plans. The project area plans outline housing developments, infrastructure improvements, and/or economic development efforts, as well as a budget that typically spans 20+ years.

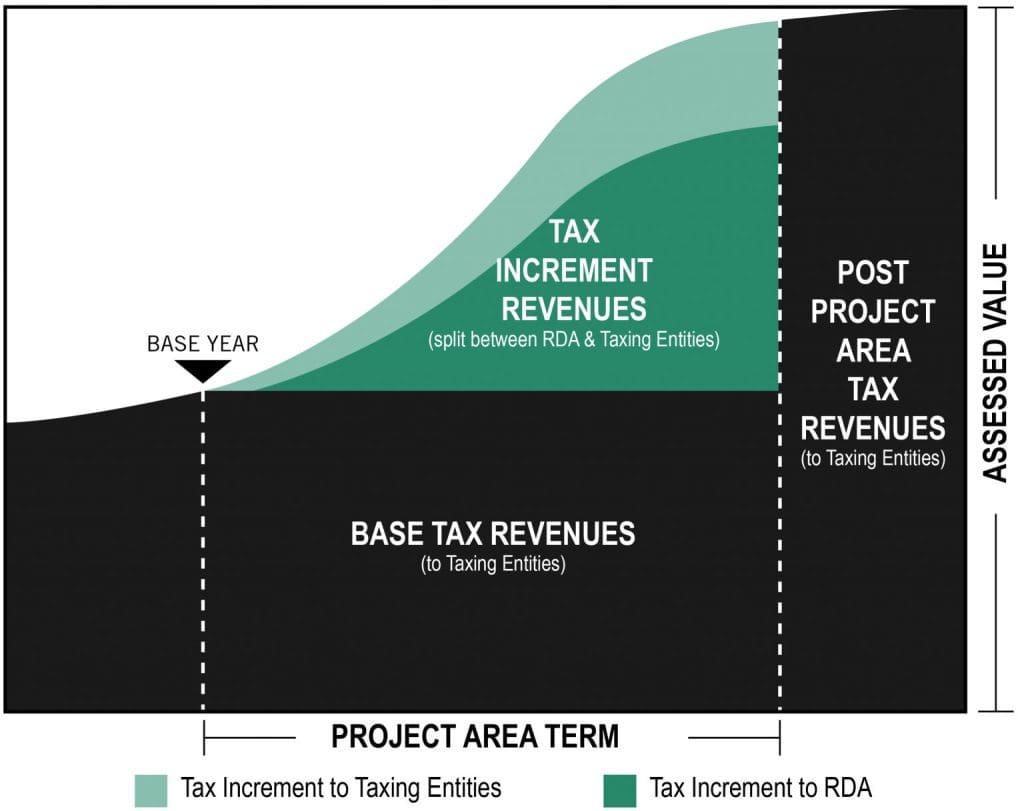

We primarily fund redevelopment projects within these project areas with property tax increment – also called “tax increment”. Tax increment is the increase in the property taxes generated within an CRA project area over and above the property taxes generated in that same area prior to the establishment of the project area. We use tax increment financing (“TIF”) within project areas to fund projects and programs that improve livability, create economic opportunity, and foster authentic and equitable communities.

We partner with the taxing entities Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County, and Salt Lake City School District to capture a portion of their tax increment to fund activities that implement shared goals within the project area plan. The establishment of a project area and the collection of tax increment funds must be approved by the CRA Board of Directors and the local taxing entities.

The tax increment generated in a project area is reinvested into that same project area, thus recycling the funds for a specified period of time, usually 20-25 years, and contributes to the area’s overall economic health and vitality. After the given amount of time, the tax increment will again be available to the local taxing entities. During the life of the project area, the taxing entities continue to receive the same amount of property taxes that they received prior to the establishment of the project area, along with any share of the increment they may have negotiated with the CRA.

Our investment in strategic project areas spur private and additional public investment which, in turn, makes way for social, economic, and productivity growth within those areas.

Annual Reports

Audit

The CRA is required by Utah Code Section 17C-1-604 to conduct, approve, and publish an independent audit of its financial condition. The primary purpose of this audit is to report the amount of tax increment collected by the CRA for each project area; the amount of tax increment paid to each taxing entity; the outstanding principal amount of bonds or loans; the amount expended for acquisition of property, site improvements, public utilities, or other public improvements; and the CRA’s administrative costs. While the last few pages of the audit provide some information on a project area basis, the majority of the audit combines revenues and expenses from all CRA activities.

While the audit serves these functions well, the final report does not reflect many of the nuances of the CRA’s finances. In the past, this has caused confusion among those reading the audit without a full understanding of other CRA-related obligations and requirements.

In particular, the audit’s reference to “unrestricted cash,” without explanation, can be misleading. The term “unrestricted,” while having a very specific meaning in accounting parlance, carries an unfortunate implication that the funds are completely available for any purpose, which is not the case.

There are three primary limitations on the use of “unrestricted cash” by the CRA:

1. Payment Of Debt Service And Tax Increment Reimbursements Through Previous Agreements

Some of the funds included in the total dollar figure represented as “unrestricted cash” are already committed through various contracts and agreements the CRA has executed. For example, the CRA periodically enters tax-increment reimbursement agreements with private developers, whereby a portion of the increased property taxes associated with a particular development will be refunded to that developer, in exchange for the developer’s provision of some public benefit, such as structured public parking, restoration of an historic building, or creation of public spaces or plazas. The funds for payment of this obligation must be budgeted each year, and, until the payment is made, those funds remain in our accounts as “unrestricted cash.” Technically, the CRA Board could elect to spend those funds for some other purpose, but doing so would entail defaulting on the CRA’s agreement with that developer. Likewise, the CRA sometimes enters Interlocal Agreements with other agencies, such as Salt Lake City, that obligate it to make ongoing payments totaling a certain amount. The funds for those payments remain as “unrestricted cash” until the payment is made.

2. Project Area Restrictions

The annual audit treats all of the CRA’s funds as a single account. But state law requires that funds generated in an CRA project area be spent within the boundaries of that area, subject to a few narrow exceptions. Therefore, while the total pooled cash of the CRA is characterized by the audit as “unrestricted,” it is, in fact, available only to be spent in the project area where it was generated. The CRA carefully tracks the funds collected by the project area of origin, and treats each project area as a separate and distinct account, ensuring that funds generated from a particular area are expended only within that area. While the CRA’s budget process described above clearly allocates expenditures by project area, the annual audit does not make this distinction, sometimes creating the inaccurate impression that the full cash balances of the CRA could be spent on a single project in a single project area.

3. Allocations Over Time — Savings-Based Approach

Another detail that is not articulated in the annual audit is the CRA’s practice of budgeting funds for large projects over time, and then paying cash for the projects when sufficient funds are accumulated to proceed. This savings-based, or cash-based approach is very conservative, and enables the CRA to tackle large infrastructure projects without having to assume debt. Because tax increment proceeds are often viewed by banks as unpredictable, borrowing against future revenues is often not possible, and, even if possible, loans are not offered on favorable terms. Therefore, the CRA’s established practice and policy is to allocate funds as available a little at a time.

This process of accumulating funds for a project often leads to large cash balances in CRA accounts. A good example is the repair and renovation of the Gallivan Utah Center. Beginning in the early 2000s, the CRA anticipated that in approximately 2008-2010, the CRA would need to undertake significant repairs and renovations to the Gallivan Utah Center. Beginning in 2006, the CRA Board allocated funds each year to be saved for that renovation project, ultimately accumulating the more than $7 million needed to complete the design and construction. Those funds were always characterized by the audit as “unrestricted cash.” Again, the saved amounts could technically be allocated by the Board for some other use, but doing so would reduce or eliminate the funds needed for the renovation and repair project.

Highlighted Projects

Our role in hundreds of redevelopment projects that have helped cultivate many of Salt Lake City’s residential, commercial, and public places is vast and varied. Sometimes our contribution has been a land write-down to stabilize or spur development in a particular area (Heber Wells Building ’80, Central Ninth Market ’16, Macaroni Flats ‘17), often we funded public infrastructure (Pierpont Walkway ’92, Pioneer Park ’95, 500 West Utility Undergrounding ’09, Central Ninth Streetscape ’23), and many times we provided gap financing through our commercial and housing loan programs (Odyssey House ’00, Broadway Park Lofts ’14, Atmosphere Studios ’16, Jackson Apartments ’21, The Aster ’23). We have also assisted public entities in acquiring community assets (Capitol Theatre ‘76, Salt Palace ’84, Children’s Museum ’09), provided grants for affordable housing (Romney Park Plaza ‘84, CitiFront ’98, Artspace Bridges ’01, Pamela’s Place ’20), and participated in tax increment reimbursement partnerships (Gateway ’01, 222 Main ’08, Delta Center ’15). Find case studies on some of our completed projects below!